Summary

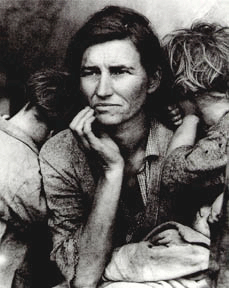

Senator Mondale was appointed to the Committee on Labor and Public Welfare in 1968, filling Senator Robert Kennedy's (D-NY) seat after his assassination. He was named Chair of the Subcommittee on Migratory Labor in 1969 and continued the work Kennedy had started in trying to improve the living and working conditions of migrant workers. As a teenager, Mondale worked alongside migrant workers in a canning factory and on farms and saw first-hand the horrible conditions and pay the workers were forced to endure. He even went so far as to try to organize the workers to ask for better pay, and quickly learned how powerless they were when they were, as he described, "packed up and shipped South, like so much bad merchandise."[1]

Powerlessness became the topic of several months of hearings over which Senator Mondale presided as Chairman of the Subcommittee on Migratory Labor. After meeting with César Chávez and visiting migrant labor camps, Senator Mondale said in an interview, "I have tried to find out for myself how migrants live, and I want to help them—really help them, not urge band-aids for the deep wounds they have."[2]

He organized the hearings in seven parts, each part focusing on a specific aspect of the life of migrant and seasonal farm workers. Instead of only hearing from experts and outsiders who had visited migrant labor camps, he insisted that the workers themselves have a voice and testify in the hearings. Many of them testified about the unsanitary conditions in which they were forced to live and the powerlessness they experienced in trying to affect any positive change. They described the sporadic education their children received and they talked about how they often ended up being in debt to the crew leaders after weeks of work due to being underpaid and overcharged for transportation. Rudolfo Juarez, a migrant worker from Florida stated, "Gentlemen, bad working conditions and low wages for generations have maintained a slave labor system which ensures that the migrant farm worker's children will have to live the same way he did and will continue to be slaves to agriculture and business."[3]After hearing reports from doctors who had investigated the health and living conditions of migrant workers, Mondale returned to the Senate floor to say, "I wish that all of my colleagues could have been in the hearing room as these doctors testified, for it is impossible to recount to you the hushed silence as they enumerated their findings. It is impossible to capture today their rage at having to recount their own experiences. There were few men and women that could sit through the testimony with dry eyes, insensitive to the realities of how we are daily destroying human beings."[4]

Due to the political climate after the election of President Nixon, Mondale did not attempt to introduce new legislation to help migrant workers, but rather tried to work to strengthen existing laws. His attempts to extend unemployment compensation and Social Security coverage to migrants and to obtain increased funding for migrant health, education and legal service programs were defeated in Congress.[5] He did succeed, however, in extending occupational hazards to farm workers.

- Robert Coles, "Champion of Powerless People - Mondale of Minnesota," The New Republic, December 25, 1971.

- Ibid.

- Migrant and Seasonal Farm Worker Powerlessness: Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Migratory Labor, 91st Cong. 92 (1969)(statement of Rudolfo Juarez, migrant farm laborer).

- 91st Cong., 2nd sess., Congressional Record 116 (October 1, 1970) at 34546.

- Finlay Lewis, Mondale: Portrait of an American Politician, (New York: Harper and Row Publishers, 1980), 190-194.