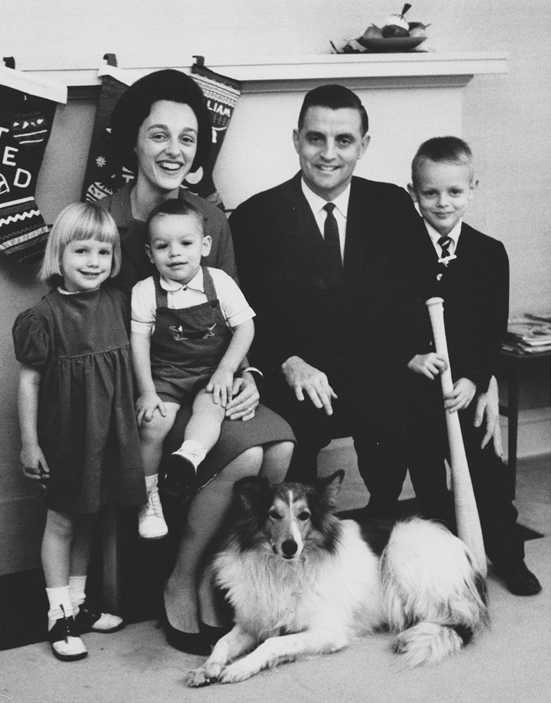

Family

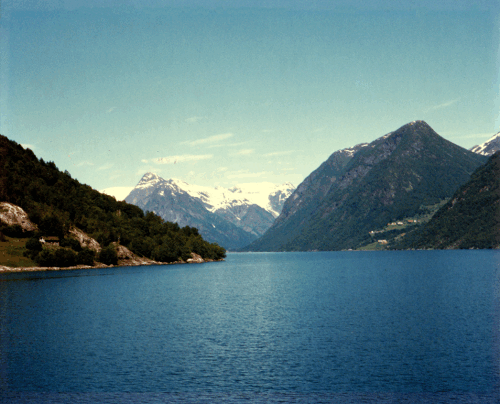

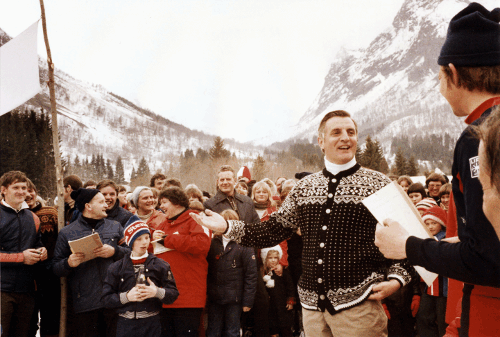

From Mundal to Mondale

Walter Mondale's great-grandparents, Frederick and Brita Mundal, came from the Mundal Valley on the Sogne Fjord in southwestern Norway. Upon arriving in the United States, they changed their name to Mundale, following the advice of an immigration official that the extra vowel would make the name "more American." The spelling again changed, this time to Mondale, when Mr. Mondale's grandfather, Ole, filed papers for land in southern Minnesota. When the papers came back from Washington, the name had been recorded as Mondale. Not wishing to take any chance of losing the land, he adopted the new name.

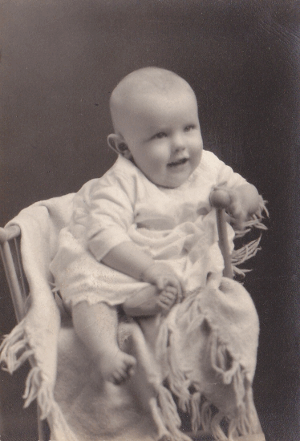

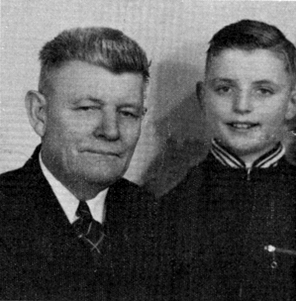

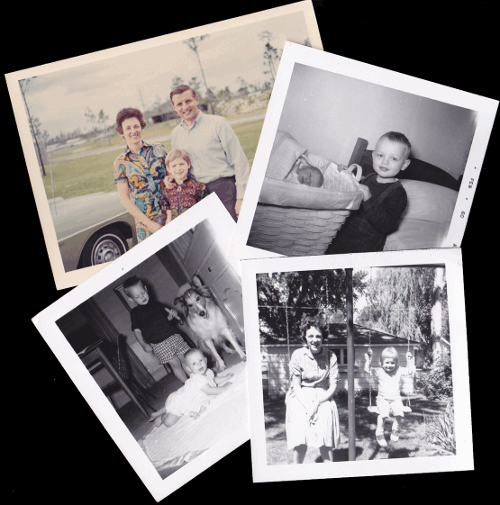

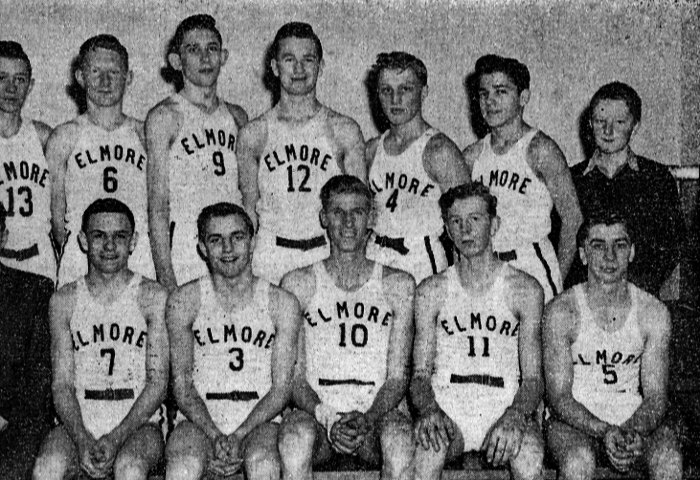

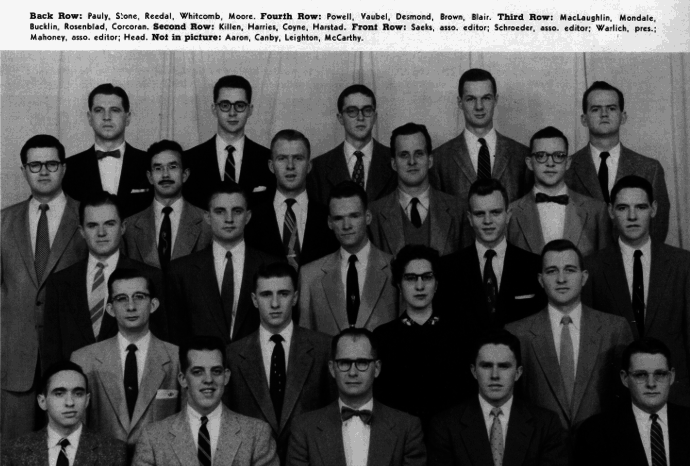

Early Years

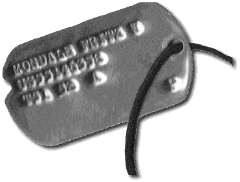

Walter Mondale volunteered for the army on September 27, 1951. He spent his basic training assisting the Company Clerk as a typist and was later rejected for a position in the prestigious Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) due to an all-too-honest interview where he expressed his disagreement with loyalty oaths.(1)

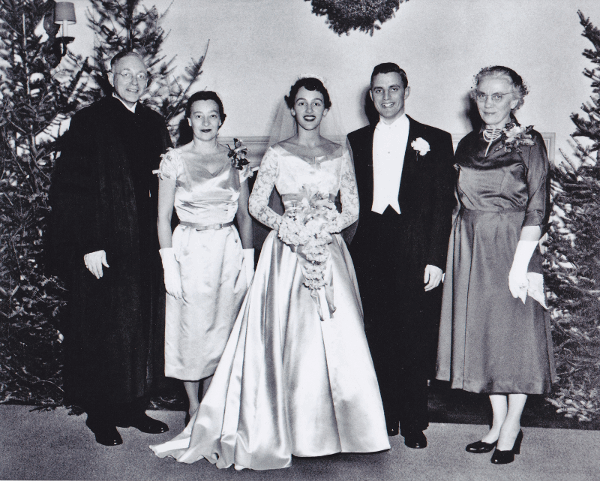

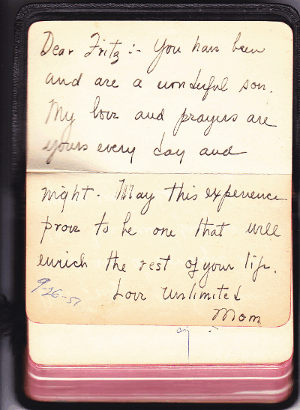

9-26-57 Mom

Attorney General (1960-1964)

Walter Mondale took the oath of office as Minnesota's twenty-third attorney general on May 5, 1960. At the age of thirty-two, he was the youngest attorney general in the nation. He had earned the reputation as the state's top political strategist by managing several Democratic campaigns in Minnesota, including Orville Freeman's 1958 successful reelection campaign for governor.

He expanded the role of attorney general by establishing separate departments for consumer protection, antitrust, and civil rights/civil liberties, each headed by an assistant attorney general, often whom he had recruited from the top national law schools.

Attorney General Mondale's first big public issue as attorney general involved a lawsuit against Marvin Kline, a former executive director of the Sister Elizabeth Kenny Foundation, and Fred Fadell, a public relations expert. Mr. Mondale's report inspired a federal investigation into charitable fund-raising and led to successful convictions on criminal charges and a reorganization of the Foundation's Board.

Mr. Mondale also discovered that the Minnesota Boys Town had been stealing money from Minnesota residents — especially senior citizens. Over a ten-year period, Minnesota Boys Town had raised $250,000 in private donations but had never spent a penny on troubled teens.

Attorney General Mondale then succeeded in getting Holland Furnace Company of Michigan's Minnesota operating license revoked after learning that salesmen for this company used the pretense of a furnace inspection to gain entrance to one's home and then, after conducting phony tests to prove the furnace was a death trap, convinced the homeowner to buy a new furnace for an exorbitant fee. Mr. Mondale used a public-nuisance law originally intended to silence barking dogs to take the company to court. Mr. Mondale won the court case and, as a result, for the first time since 1911 an out-of-state corporation had its authority to do business

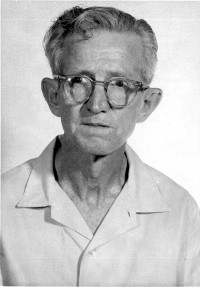

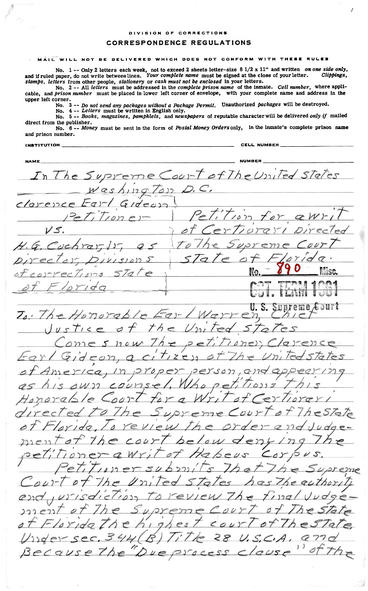

In 1962 Florida's attorney general, Richard Ervin, sent a letter to the attorney general in each state requesting support for his argument that the Constitution did not require states to provide legal counsel. Mr. Ervin was responding to a petition sent to the Supreme Court by Clarence Earl Gideon, a "small-time gambler, a sometime hobo, and an 'ex-con.'"(2) Gideon had been charged with breaking and entering into a Panama City, Florida pool hall and stealing money from the hall's vending machines. At trial, Mr. Gideon requested the representation of an attorney since he could not afford one. He was told that the state wasn't required to provide him with an attorney because his wasn't a death penalty case. He was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison. Mr. Gideon wrote his petition while incarcerated.

Attorney General Mondale disagreed with Mr. Ervin's position and, at the urging of University of Minnesota Law School professor Yale Kamisar, composed a letter in which he argued: "I believe in federalism and states' rights too. But I also believe in the Bill of Rights. Nobody knows better than an attorney general or a prosecuting attorney that in this day and age, furnishing an attorney to those felony defendants who can't afford to hire one is fair and feasible."(3) Mr. Mondale sent his letter to the attorneys general in every state and, with the help of Massachusetts Attorney General Edward McCormack, collected twenty-two signatures in support. A brief Mr. Mondale, Yale Kamisar, and Mr. McCormack submitted in favor of the defendant, Clarence Gideon, figured significantly in the Supreme Court's decision to reverse and remand Mr. Gideon's conviction and to establish the law that everyone has the right to counsel.

In his memoir, The Good Fight, Mr. Mondale writes: "The Gideon brief was probably the most important single case that I pursued in four years as attorney general, and it certainly represented higher stakes than anything a young Minnesota politician expected to handle during his first years in public office. But it typified the era in which I entered politics....people were warming to the view that public office could be used to protect the disadvantaged and advance the rights of ordinary people."(4)

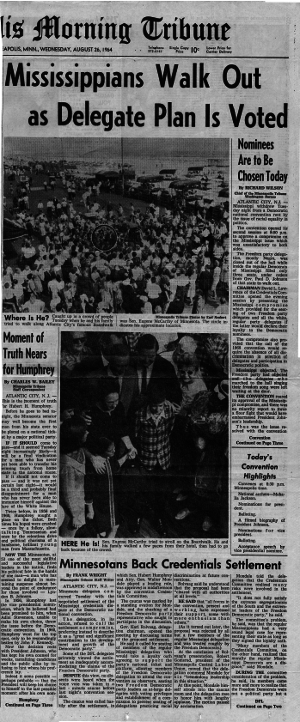

Mr. Mondale was a key player at the 1964 Democratic Convention in negotiating and instituting a compromise between the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and the Mississippi Regular Democrats. The MFDP would receive two at-large seats with no voting rights, while the white delegation sent by the official Democratic Party would take its seats after signing a loyalty oath. Neither side was happy with the compromise: all but three of the regular Mississippi delegation walked out of the convention and the MFDP felt betrayed. As a result, a civil rights commission was established to prevent state delegations that practiced discrimination from taking part in any future conventions.

Senator (1964-1976)

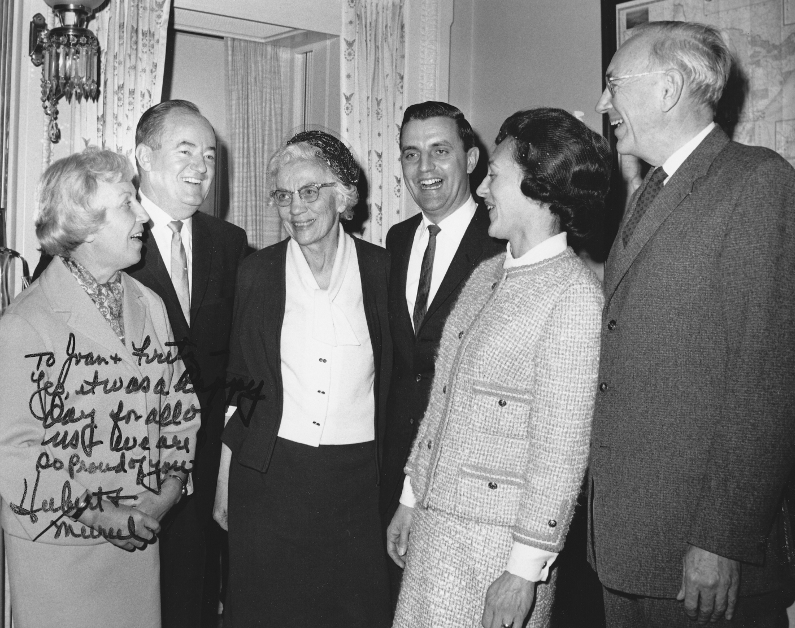

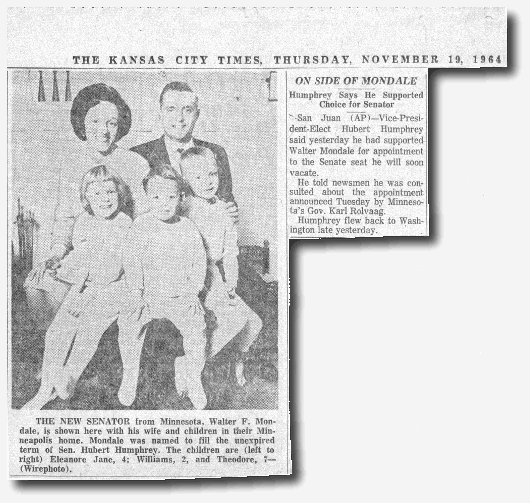

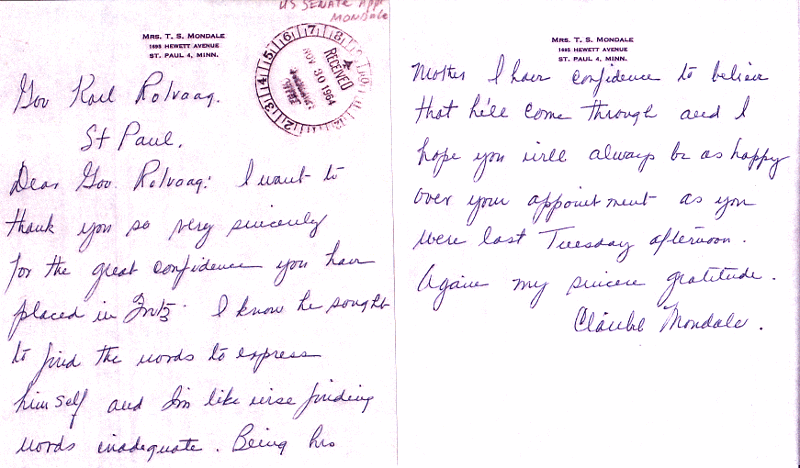

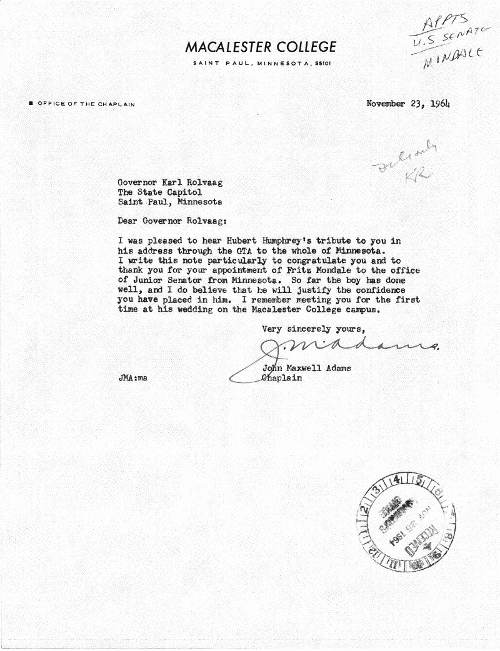

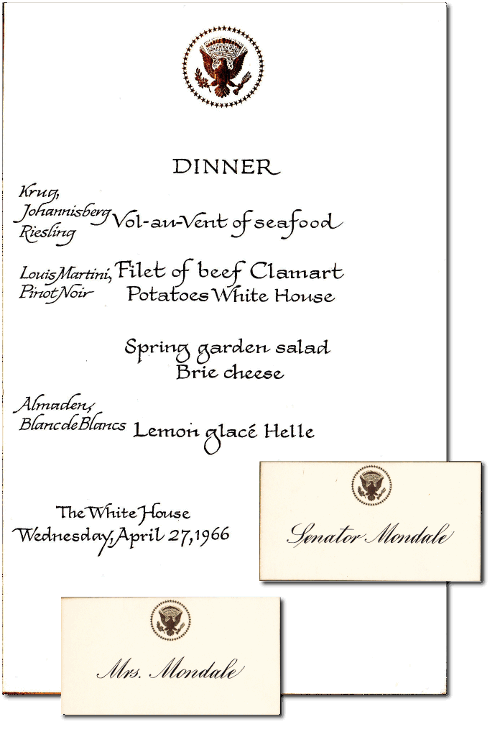

Walter Mondale became a U.S. Senator from Minnesota in 1964 when he was chosen by Governor Rolvaag to fill the Senate seat vacated when Hubert Humphrey became Vice President. He was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1966 and re-elected in 1972.

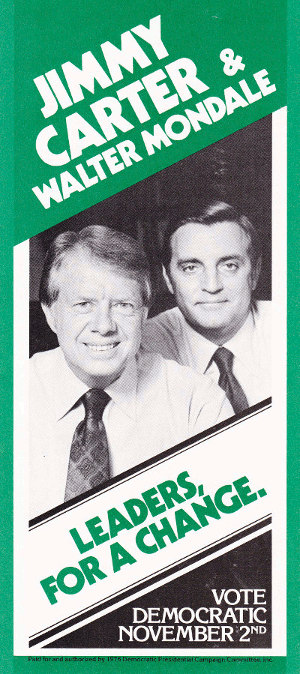

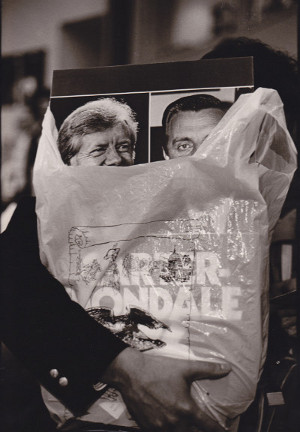

Vice President

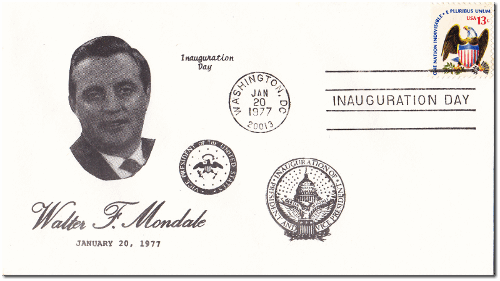

Walter Mondale was elected Vice President under Jimmy Carter in 1976. President Carter and Vice President Mondale defined the modern vice presidency, transforming the office into an integral part of the executive branch. Vice President Mondale was a key participant in the negotiations between Egypt and Israel that resulted in the Camp David Accords.

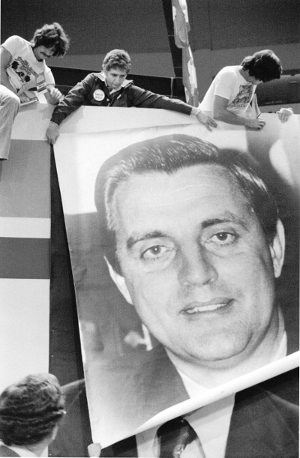

'84 Campaign

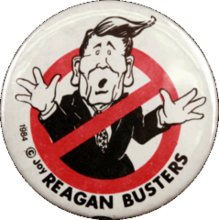

As the Democratic presidential nominee in 1984, Mr. Mondale made history by selecting a woman, Geraldine Ferraro, as his running mate. Despite his "landslide" loss to incumbent president Ronald Reagan, Mr. Mondale focuses on the positive results of the 1984 election: "What happened in San Francisco in the summer of 1984 didn't merely lift Geraldine Ferraro and Jesse Jackson to extraordinary heights; it didn't merely create new opportunities for a cohort of women and people of color in politics. It changed the expectations of every generation that followed them and allowed them to see America as a different and more hopeful place."(5)

Elder Statesman

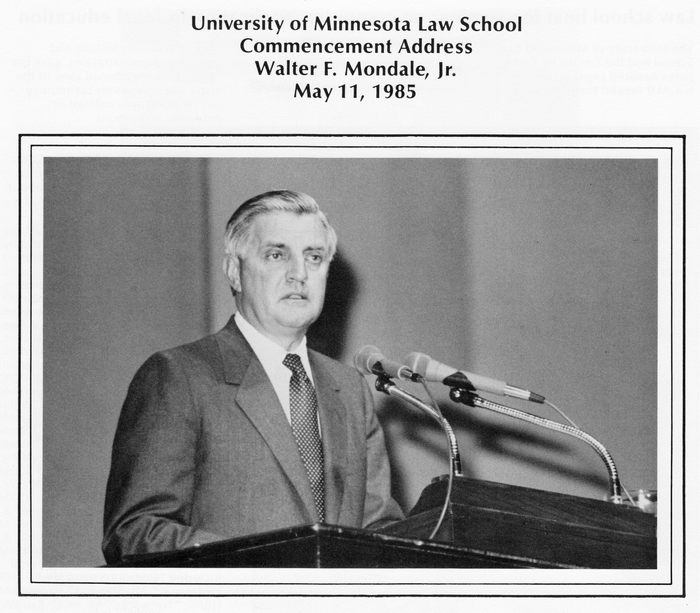

University of Minnesota Law School Distinguished Alumnus

"The test of a great law school is whether it produces special citizens—lawyers with hearts as well as minds—who assume the responsibility to move our society to higher plateaus of justice. This is such a school."

Walter F. Mondale, University of Minnesota Law School Commencement Address, May 11, 1985

"What I learned at the University of Minnesota Law School opened the door to my world and set me on my road to the State Capitol, the Congress, the White House, the presidential campaign, to Japan, and finally back home again. My years here changed my life forever. My teachers not only taught me about the law, but from their friendship and example, I left here with a far better idea of why honesty, decency, learning, service, and justice are so crucial to all of us. For me it was magic and it still is."

Walter F. Mondale, Dedication of Walter F. Mondale Hall, May 17, 2001

Conversation with Vance Opperman ('69) on Civility and Public Discourse

January 26, 2011. Video: runtime - 31 minutes

Topics covered include Gideon v. Wainwright, the Church Committee, and Civil Rights; credit: University of Minnesota Law Library Archives.

Download transcript for Conversation with Vance Opperman ('69) on Civility and Public Discourse.

Walter F. Mondale and Robert A. Stein, Dean, University of Minnesota Law School, at the Law School's centennial celebration, October, 1988; credit: University of Minnesota Law Library Archives

Walter F. Mondale listening to Senator Patrick Leahy, University of Minnesota Law School's celebration of Mr. Mondale's 80th birthday, April, 2007; credit: University of Minnesota Law Library Archives

"There's something everybody can attest to: Fritz Mondale is a good man, whose decency elevated every institution in which he served. Who he is has everything to do with what he achieved.

When Fritz entered politics he did it for the right reason: to make life better for other people. . . He was and he is well-liked on both sides of the aisle. Fritz's dad taught him that your integrity is everything. Boy that lesson stuck. He kept his word."

Patrick Leahy, University of Minnesota Law School's celebration of Mr. Mondale's 80th birthday, April, 2007

"When I got sworn in as a senator, it was Walter Mondale who escorted me onto the Senate floor, and I can't think of a better way to begin my career...

[In the Senate], he was a great champion for our Minnesota values of fairness and decency and opportunity."

Amy Klobuchar, University of Minnesota Law School's celebration of Mr. Mondale's 80th birthday, April, 2007

- Steven M Gillon, The Democrats' Dilemma: Walter Mondale and the Liberal Legacy (New York: Columbia University Press, 1992), 43.

- Yale Kamisar, "Gideon v. Wainwright: A Quarter Century Later," 10 Pace Law Review (1990), 2.

- Walter F. Mondale, The Good Fight: A Life in Liberal Politics (New York: Scribner, 2010), 6.

- Ibid, 7.

- Ibid, 308-309.