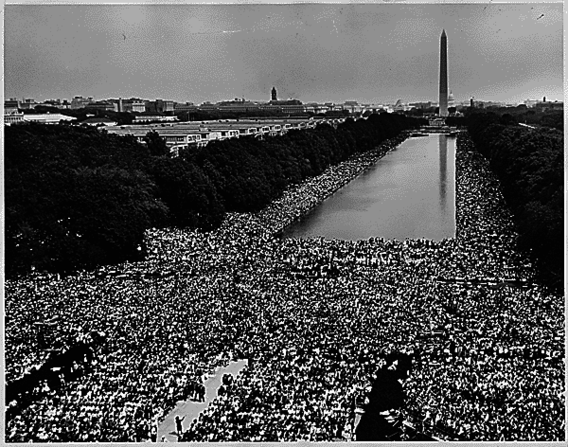

credit: National Archives and Records Administration

While Senator Mondale's signature contribution to civil rights is fair housing, he was instrumental in advancing work in other areas of civil rights as well. In March 1965—in one of his earliest speeches in the Senate—he condemned the violence and abuse endured by a peaceful group of civil rights protestors.[1] Several months later, he spoke in response to the 1965 riots in Los Angeles. He addressed the need to immediately restore order, but also to understand the source of the riots: "If we put down the violence while ignoring the conditions which breed violence, then our action today will be but a prelude to greater disasters tomorrow. We must go further, we must attack the seeds of poverty and discrimination which cause such tragedies, if we are not to reap a further harvest of bitterness and shame for America."[2] Two years later, he and Senator Harris (D-OK) proposed a commission to study civil strife and in 1970 he chaired the Select Committee on Equal Educational Opportunity. As chairman of the committee, Senator Mondale oversaw fifty-one days of hearings that addressed desegregation of public schools and the racial imbalance in urban schools due to de facto segregation and housing discrimination.

Senator Mondale refused to compromise on his beliefs regarding civil rights. When asked if he would yield during a debate on desegregation, Senator Mondale responded, "I will be glad to yield in a minute. I want to get this point home, because I would rather lose my public career than give up on civil rights. For 10 years as attorney general of my State and as a U.S. Senator, I have regarded it as a religious responsibility to treat every man as an equal. And I am offended by racial segregation, wherever it exists."[3] Two days later, expressing dismay at the passage of the Stennis amendment, which he believed would slow desegregation, he stated, "I was brought up by my father in a family which believed that everyone was a child of God and was entitled to the dignity that flowed from that concept. I was taught that a man's color was irrelevant. I will continue to press this cause, because unless we can sustain it, the promise of America will be lost."[4] And again in that same debate, Senator Mondale declared, "Whatever the politics, I am one of those who believes that there can be no compromise on the issue of human rights, that this is one issue that is worth everything, including one's public office."[5]

Senator Mondale was a vocal critic of Richard Nixon's stance on civil rights even before Mr. Nixon was elected to the presidency: "If Mr. Nixon has a chance to practice what he preaches, we are in for more segregation, not less; for poorer education for Negro children, not better; we are in for a backward step, rather than a forward step."[6] He continued to be critical of the Nixon administration's policies on civil rights: its lack of enforcement of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964; its disregard for the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment; its contempt for Supreme Court rulings on school desegregation.

His pressure on the administration was relentless. In 1969 Senator Mondale called attention to the fact that the Department of Defense had awarded contracts to three Carolina textile firms that were guilty of discrimination. He was one of five senators who in 1969 wrote a letter to Robert Finch, the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, expressing concern over the administration's stand on school desegregation and urging the secretary to implement the desegregation guidelines "firmly and fairly." That same year, he urged Clifford Hardin, the Secretary of Agriculture, "to tell us specifically what steps he intends to take to improve the dismal civil rights record of his Department" before Congress appropriates funds for USDA programs. He adamantly opposed President Nixon's nomination of Judge Harrold Carswell in 1970 to the Supreme Court: "What is unique about Judge Carswell's nomination is that it raises the question of whether a person who has a lifetime record—a personal record as well as a judicial record—of antagonism and hostility to human rights and civil rights, and to the enforcement of the law of the land, and specifically to orders of the circuit court under which he operated, should be permitted to serve on the highest court of the land. I believe that it would be exceedingly unwise and disastrous to do so."[7] At one point, Senator Mondale denounced the administration's tactics in filibustering a bill on school desegregation: "I think it is an insult to the Senate, an insult to the education subcommittee, and an insult to the relationship that a healthy government needs in trying to deal in this fashion with this most controversial and explosive question of our time—the question of desegregation and integration. I want to work with this administration, but I cannot recall in the 6 years I have been in the Senate seeing an issue dealt with as shabbily as this one has been."[8]

A public face in the fight for civil rights and school desegregation, Senator Mondale asserted that "it is not a question of what some of us would like to do or not like to do. It is a question of whether we intend to uphold the Constitution. It is a question of whether we believe in ... law and order; a question of whether there are some laws we enforce and some laws we ignore, and some laws we implement and some laws we obstruct."[9]

Citing numerous examples of successful school integration, Senator Mondale fully supported the Education Amendments of 1971. When the House introduced "anti-integration" amendments that would prohibit federal funds for transportation to achieve racial balance in schools, he accused it of turning "a hopeful equal education opportunity bill into a school segregation bill." He argued that "the issue is not busing or racial balance. The issue is whether we will build on hopeful examples of successful integration to make school desegregation work—or endorse segregation on principle; whether we will help the courts to avoid educational mistakes—or leave them to face the complexities of school desegregation alone. But beyond that, the issue was, and is, racism. The issue is whether we are going to have as the Kerner Commission warned two societies, one white, and one for the rest of us."[10]

Despite his support for many of the programs funded in the Education Amendments of 1971 and his recognition that the bill was "perhaps the single most important education bill ever before Congress," he could not bring himself to support it. He was critical of three amendments left in the bill that would "cripple the capacity of federal courts and agencies to remedy racially discriminatory school segregation under the Constitution and title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964."[11] He argued that "the freedoms found in the Constitution, the freedoms fundamental to American life, are in a real sense non-compromisable. They are on a different level, a different plateau, and bear a different value from other disputes. I do not think we can compromise the basic human rights even for a magnificent program of higher education such as that embodied here. Therefore, in sorrow, and not in anger, I cannot support the conference report."[12]

Senator Mondale's core belief in "the freedoms fundamental to American life" led him to cosponsor the Equal Rights Amendment in 1972: "We have made great strides in this country in recent decades toward eliminating the legal basis for discrimination against members of minority groups. But we still have a long way to go to provide the same protection to the majority of our population—the 51 percent who are women.... Discrimination against women is a documented, proven fact in many aspects of American life and a cruel reality that mars the ambitions of untold numbers of American women."[13] In 1973 he introduced the Women's Educational Equity Act, "seeking to eliminate discrimination in many phases of education."[14] Two years later he introduced the Women's Vocational Education Amendments which provided "a new and much-needed emphasis on women's roles within the vocational education system," and aimed "to eliminate existing barriers to the full participation of both sexes in vocational education programs."[15]

- 89th Cong., 1st sess., Congressional Record 111 (March 8, 1965) at 4350-4352.

- 89th Cong., 1st sess., Congressional Record 111 (August 17, 1965) at 20625.

- 91st Cong., 2nd sess., Congressional Record 116 (February 17, 1970) at 3581.

- 91st Cong., 2nd sess., Congressional Record 116 (February 19, 1970) at 4133.

- 91st Cong., 2nd sess., Congressional Record 116 (February 19, 1970) at 4137.

- 90th Cong., 2nd sess., Congressional Record 114 (September 23, 1968) at 27823.

- 91st Cong., 2nd sess., Congressional Record 116 (March 20, 1970) at 8384.

- 91st Cong., 2nd sess., Congressional Record 116 (December 31, 1970) at 44418.

- 91st Cong., 2nd sess., Congressional Record 116 (February 28, 1970) at 5378.

- 92nd Cong., 2nd sess., Congressional Record 118 (February 18, 1972) at 4577.

- 92nd Cong., 2nd sess., Congressional Record 118 (May 24, 1972) at 18845.

- 92nd Cong., 2nd sess., Congressional Record 118 (May 24, 1972) at 18846.

- 92nd Cong., 2nd sess., Congressional Record 118 (March 17, 1972) at 8894.

- 93rd Cong., 1st sess., Congressional Record 119 (October 2, 1973) at 32484.

- 94th Cong., 1st sess., Congressional Record 121 (November 3, 1975) at 34668.