Excerpt 1

"I suppose my views are colored in this by my own background. My dad was a Methodist minister. And although we grew up in rural areas, he always taught us the importance of believing in human rights. And I can remember as a young child making my first disparaging remark about a Negro, and he gave me my first lesson in civil rights. I got my pants tanned. And all through my public career I have been of the opinion that human rights are really nonnegotiable, just like free speech."

U.S. Congress. Senate. Committee on Banking and Currency. Fair Housing Act of 1967: Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Housing and Urban Affairs. 90th Cong., 1st sess., August 21, 22, and 23, 1967.

Excerpt 2

"I believe that this Nation is as sick as it has ever been. I believe that one of the first and necessary steps to its cure is an understanding of the vast character of the problem that lies ahead of us. It literally involves the remaking of our Nation. Unless we understand that, unless we approach it with that in mind, I fear that all our remedies will fall far short of the mark....

This effort will require the best that everyone in society can provide, the best of the private and the public sectors, the best of local and State governments, the best of private foundations, unions, cooperatives, churches, and all of the other organizations and sectors of American society.

We have now begun to pay the price of at least a winter of social neglect. The answer cannot be simply found in the suppression of the riots as important and indispensable as that is because, as the Washington Post editorial stated this morning: The question is whether a nation of free men can achieve order and social justice as well." 90th Cong., 1st sess., Congressional Record 113 (July 25, 1967) at 20200.

Excerpt 3

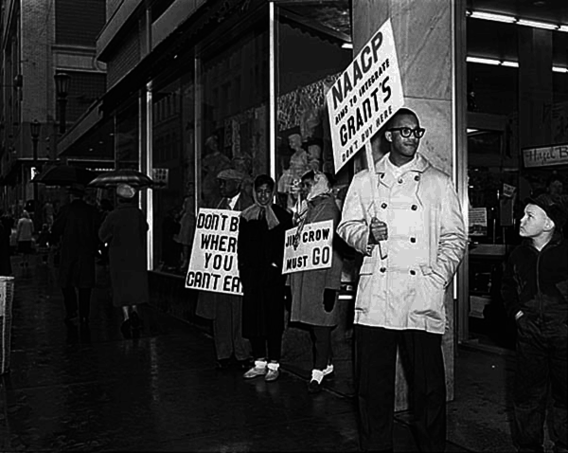

"We should remember that the law, in addition to being a coercive force, must function as well as a teacher. By directing the actions of the citizen, it must produce a change in attitude. Without a change in public attitude, all the legislation in the world cannot guarantee racial equality. Up to now, we have accomplished the legal abolition of the practices of segregation, and we have obtained a grudging tolerance, a lowering of formal legal barriers, a removal of 'white only' signs from drinking fountains, school doors, and waiting rooms. We must do more than achieve minimum compliance with the law, motivated more by the fear of jails than by an honest request for one's fellow man. While this is necessary and worthy of our first efforts, it is merely an initial goal.

Beyond this lies the true meaning of 'integration.' Beyond this lies acceptance-acceptance of every fellow citizen as a man with heart and mind, body and soul. This goal may remain unreached when every lunch counter in the Nation has dropped its formal barriers to Negro entry.

It may remain unreached when every Negro is allowed the full and equal right to vote and participate in the political process of his State and city. It may, as well, remain unreached when the last Negro has stepped off the sidewalk and tipped his hat to the passing white man. But we must begin now to reach the day when we have a nation in which every man is accepted at his own worth." 89th Cong., 1st sess., Congressional Record 111 (August 10, 1965) at 19760.

Excerpt 4

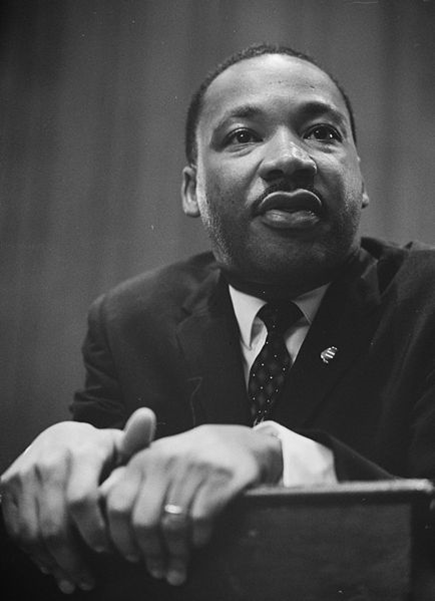

"More than any other man in this Nation's history Martin Luther King brought the Negro to America's conscience. He became the visible of the invisible men. It took a man of unquestioned courage and conviction, a man of irreproachable character, a man of unmatched eloquence, a man of God to first confront us with the racism and repression in our own country.

Martin Luther King led his people to new self-respect. Like Moses, he was a man with a vision of the promised land. Moses at the close of his life stood on a mountaintop and looked upon the better land he had envisioned. To Moses, scripture says, the Lord spoke, saying:

I have let you see it with your own eyes,

but you shall not go over there.Alluding to these words two nights ago in Memphis, King spoke:

It doesn't matter with me because I've been to the mountain top . . .

I may not get there with you, but I want you to know tonight that we as a people

will get to the promised land.Martin Luther King died in his fight to make men free. The foremost proponent of a nonviolent confrontation between the races is dead. His generosity to the white man, his belief in the basic good will of all men, and his dramatic, nonviolent action enabled him to speak to both races." 90th Cong., 1st sess., Congressional Record 114 (April 5, 1968) at 9138.

Excerpt 5

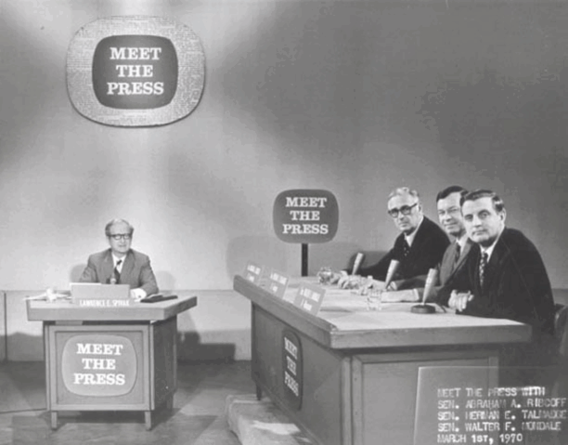

"I would rather lose my public career than give up on civil rights.

For 10 years as attorney general of my State and as a U.S. Senator, I have regarded it as a religious responsibility to treat every man as an equal. And I am offended by racial segregation, wherever it exists." 91st Cong., 2nd sess., Congressional Record 116 (February 17, 1970) at 3581.

Excerpt 6

"Whatever the politics, I am one of those who believes that there can be no compromise on the issue of human rights, that this is one issue that is worth everything, including one's public office." 91st Cong., 2nd sess., Congressional Record 116 (February 19, 1970) at 4137.

Excerpt 7

"I hope and believe this is a country in which we seek to live together as Americans, rather than to be divided on the utterly irrelevant, disruptive, and undemocratic grounds of race and color.

I do not know what the politics of human rights is today. I suspect it is less popular than it has been for many years.

I sense a feeling of agony, frustration, and despair which generates a sense of antagonism and separatism that we have not seen in this country for a long time.

I do not know where it will take us. But I do know this. I in no way intend to reduce my efforts or my commitments to the cause of a country in which color is irrelevant. I do not think we can have a democracy that is not color blind.

I was brought up by my father in a family which believed that everyone was a child of God and was entitled to the dignity that flowed from that concept. I was taught that a man's color was irrelevant.

I will continue to press this cause, because unless we can sustain it, the promise of America will be lost." 91st Cong., 2nd sess., Congressional Record 116 (February 19, 1970) at 4133.

Excerpt 8

"I think that we had so many tragic efforts in national education policy that it is terribly important, particularly as it affects race, that we use this opportunity to define it in a precise way which endorses a national objective of quality integration. In other words, that we agree, as Americans, that we are going to begin to be educated together, live together, and treat one another as equals and that is our objective, rather than a negative sort of body mixing."

U.S. Congress. Senate. Committee on Labor and Public Welfare. Emergency School Aid Act of 1970: Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Education. 91st Cong., 2nd sess., June 9, 1970. p. 54.

Excerpt 9

"Mr. President, for nearly 2 years, I have served the Senate as Chairman of the Select Committee on Equal Educational Opportunity. It has been a painful 2 years for me, and I believe for other members of the committee as well. We have heard almost 300 witnesses on the issues which the Senate confronts today. And we have learned a great deal about success and failure in American public education.

We have tried to look deeply into the workings of public education in all parts of this country. We have not concentrated on the South by any means.

And, I am left with a deep conviction—that American education is failing children who are born black, brown, or simply poor." 92nd Cong., 2nd sess., Congressional Record 118 (February 18, 1972) at 4574.

Excerpt 10

"A generation of American girls is growing up reading biased textbooks; being guided by counselors who often label particular careers as either 'masculine' or 'feminine'; receiving less than their share of physical education because it is generally thought to be more appropriate and necessary for boys." 93rd Cong., 1st sess., Congressional Record 119 (October 2, 1973) at 32484.

Excerpt 11

"A large portion of my career in the Senate has been devoted to the study of education and to attempts to improve the system and make its benefits accessible to all Americans.

In the 1960s—many years too late—we finally became aware as a Nation of the failure of our educational system to serve the disadvantaged child, the migrant child, the Indian child living on a reservation, the black and Chicano children in inner city ghettos and isolated rural areas.

In the Congress, in the executive branch, and in the education establishment, momentum developed for the creation of new programs that would provide all of these children with the opportunity for a decent education....

So it has been an unsettling experience for many of us to learn—as a result of the work done in recent years by the women's movement—that for years the educational system has actually been discriminating against the majority of our population—women."

U.S. Congress. Senate. Committee on Labor and Public Welfare. Women's Educational Equity Act of 1973: Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Education. 93rd Cong., 1st sess., October 17 and November 9, 1973. p. 1-2.